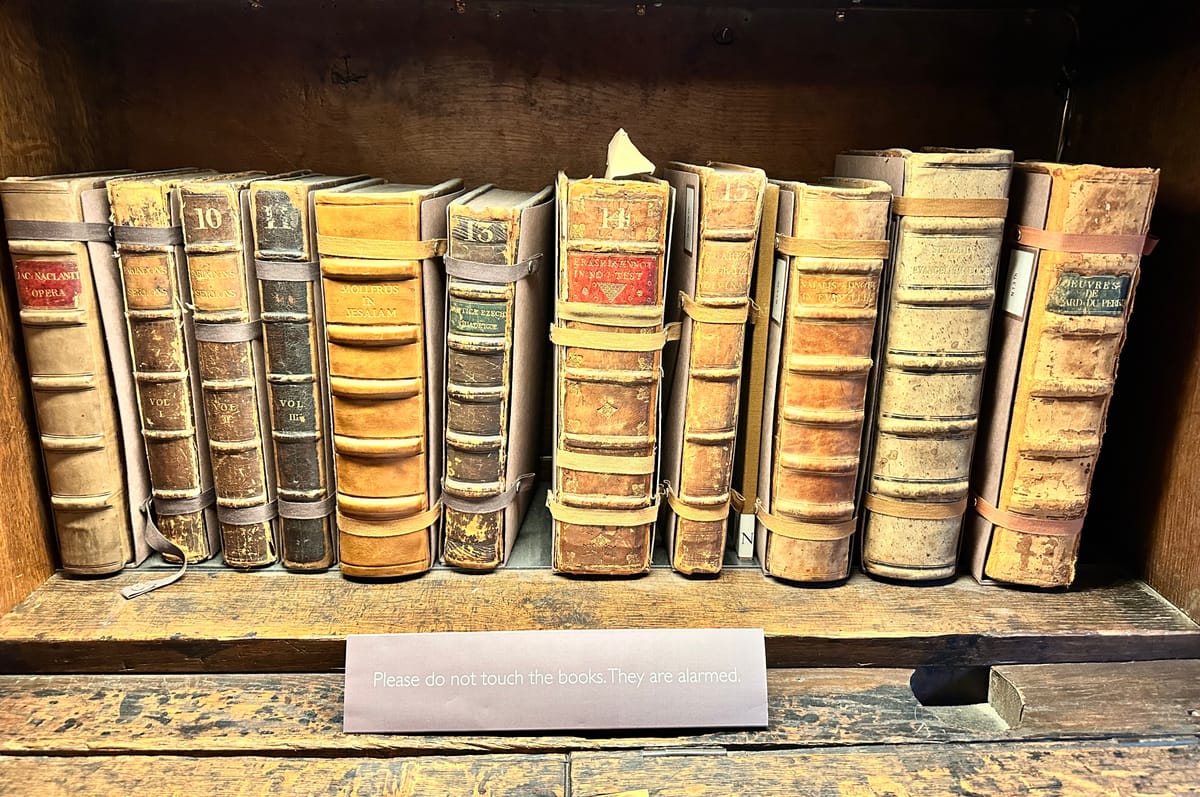

Please do not touch the books. They are alarmed

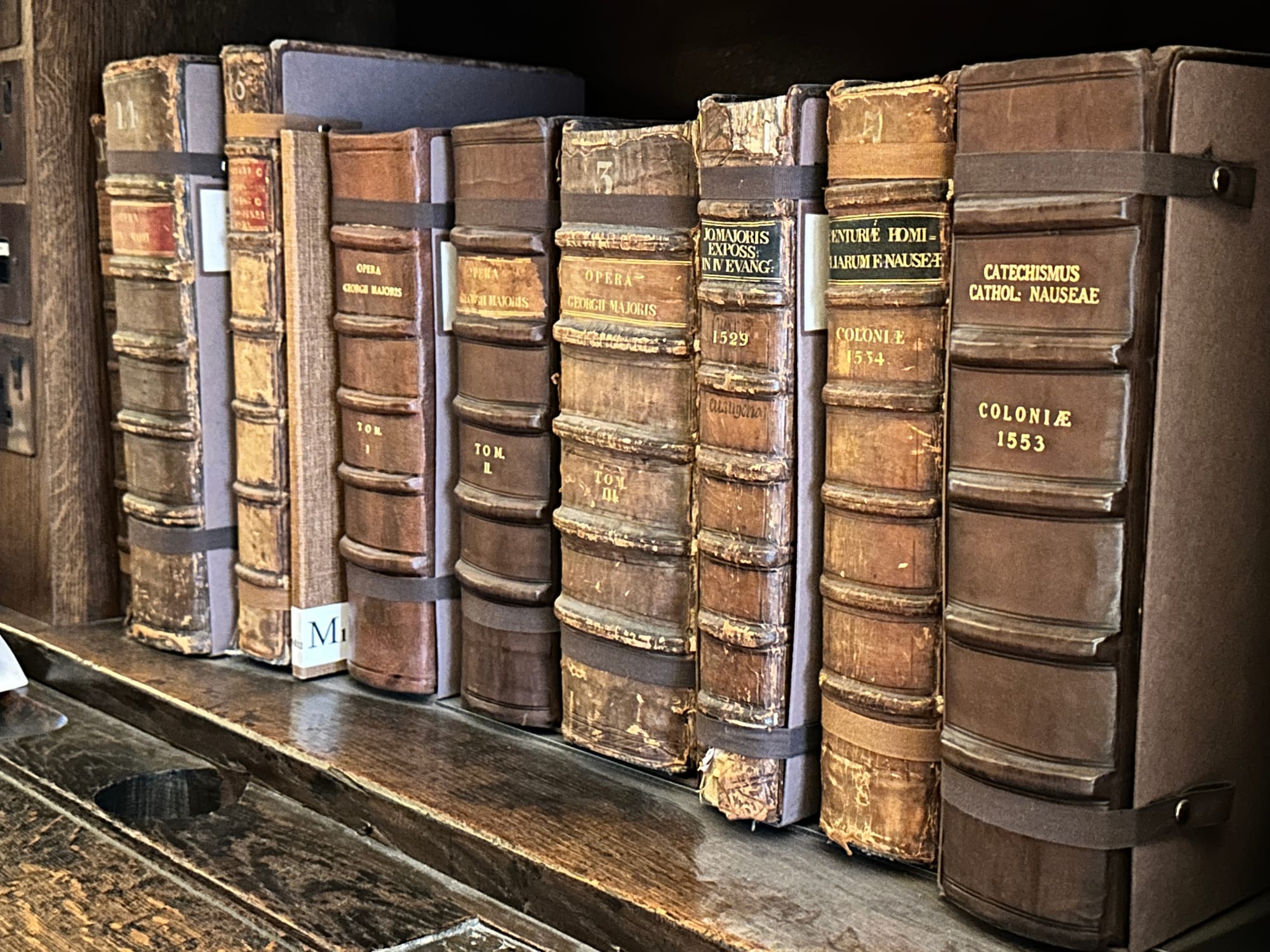

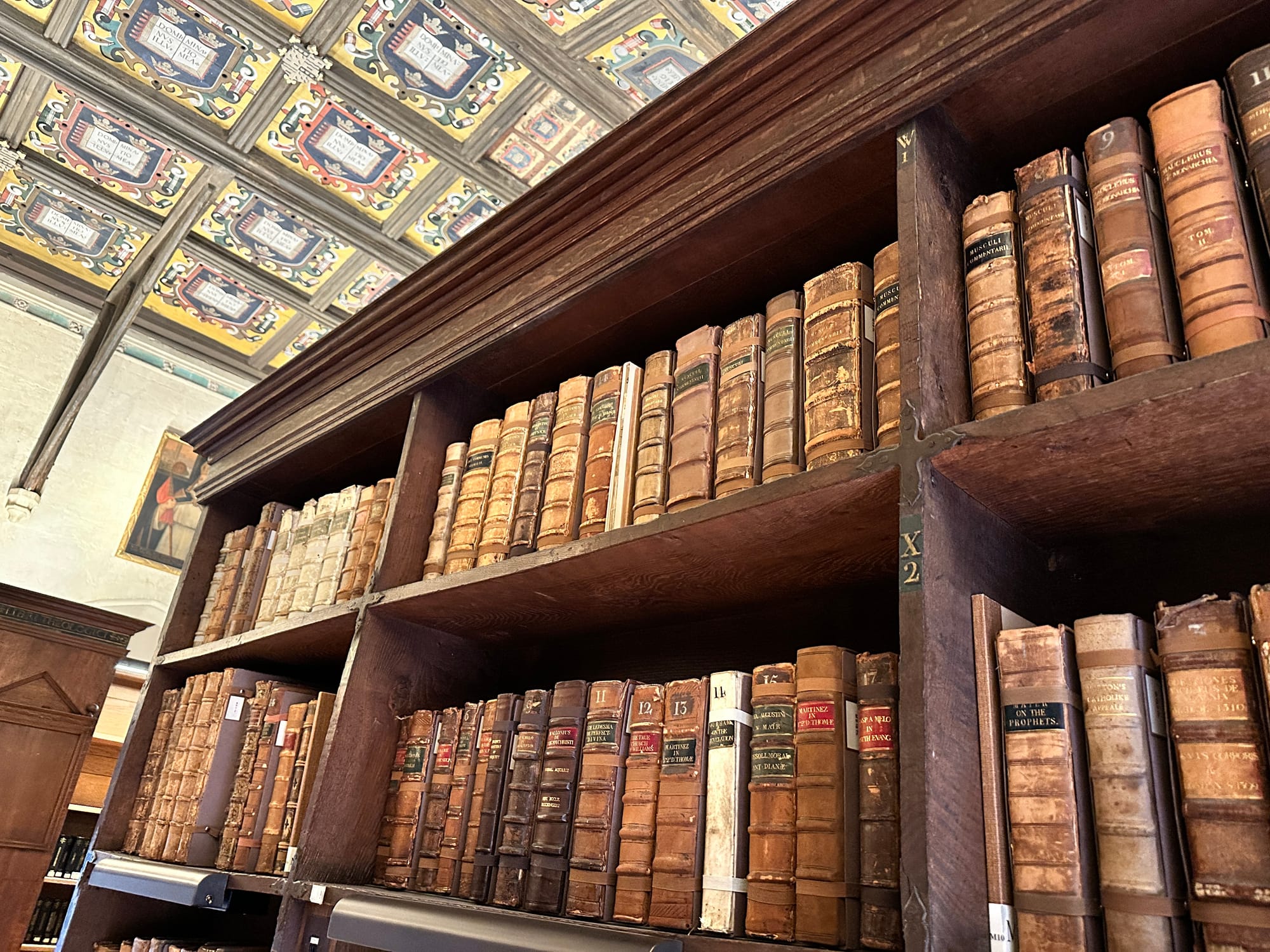

This sign sits in front of rare manuscripts at Duke Humfrey's Library in Oxford - a historic reading room where only students are permitted, and even then, they may sit near the books but never touch them. I can't even bring my own bag into the room; I must transfer what I need for study into a transparent bag provided by the library and store my personal belongings in a locker. One pound, returned once the locker is unlocked. Oxford protects these treasures through layers of restriction: controlled access, physical barriers, and yes, alarms. What is most valuable is shielded from unnecessary exposure.

This principle of careful stewardship stands in stark contrast to a recent security incident at OpenAI. The company reported yesterday that one of its third-party vendors, Mixpanel, suffered a misconfiguration that allowed an unauthorised individual to export customer-identifiable information, including names, email addresses, and user or organisation IDs. The affected population included some ChatGPT API users and a small number of ChatGPT Team accounts.

This incident reflects a broader trend identified by Gartner, which notes that third-party and supply-chain vulnerabilities, together with risks of data leakage and unintended exposure, are among the most significant AI-related cyber threats facing security leaders today. As organisations rush to implement agentic AI, whether building capabilities in-house or partnering with external providers, these risks multiply.

Gartner predicts that, through 2029, over half of successful cyberattacks against AI agents will exploit access-control issues, often using prompt-injection techniques. When sensitive information travels through external analytics tools, vendor-hosted AI features, or logging systems, organisations take on risks that are not entirely within their control - precisely the kind of scenario that will become increasingly common as AI adoption accelerates.

Organisations need the same disciplined approach to protecting data that Oxford applies to its manuscripts:

- Strong third-party risk management

- Transparent vendor practices

- Clarity about how AI systems handle data

- Rigorous controls across the AI supply chain, including monitoring contractual protections, and strict limits on data sharing.

But organisational safeguards are only part of the equation. Individual users must also take responsibility for their interactions with AI systems. This means:

- Never share sensitive business information, personal data, or proprietary content in prompts unless you fully understand where that data goes and how it will be stored.

- Treat AI tools like public forums: assume your inputs could be logged, analysed, or used for training unless you have explicit assurances otherwise.

- Review privacy settings and decide whether you want the model to learn from your conversations; if you don't, disable this option in settings. Most AI platforms now offer controls to opt out of data sharing and model training, but these features aren't always enabled by default.

- Be especially cautious with free or open-source AI services, as they may use different data-handling practices than enterprise versions.

There's nothing inherently wrong with AI. It's a tool with remarkable capabilities and, like any tool, it has its limitations. Consider what would happen if Oxford opened the doors of Duke Humfrey's Library to the general public, removed the alarm sign, and disabled the security systems entirely. The manuscripts themselves wouldn't change, but the risk of damage, theft, or misuse would increase dramatically.

The same principle applies here. AI can be used for tremendous good or harm, and it's our choice: the outcome depends on the safeguards we implement and the boundaries we set. The technology isn't the problem; it's how we choose to protect what matters when we use it.

Your data is your rare manuscript. Treat it accordingly.